Halloween is among the oldest traditions in the world as it touches on an essential element of the human condition: the relationship between the living and the dead. The observance evolved from ancient rituals marking the transition from summer to winter, thereby associating it with transformation, which is still a central theme of the holiday.

Every recorded civilization has created some form of ritual observance focused on what happens to people when they die, where they go, and how the living should best honor those who have passed or respond to the dead who seem unwilling or unable to move on. Countries around the world today celebrate Halloween in one form or another, from Mexico's Day of the Dead to China's Tomb Sweeping Day. The modern-day observance of Halloween in countries such as the United States and Canada – where this tradition is most popular – share in this ancient tradition, even though some aspects of the holiday are relatively recent developments and can be traced back to the Celtic festival of Samhain.

Christian groups through the years have routinely attempted to demonize and denigrate the observance, in part by repeating the erroneous claim that Sam Hain was the Celtic god of the dead and Halloween his feast. This error comes from the 18th-century British engineer Charles Vallancey, who wrote on the Samhain festival with a poor understanding of the culture and language, and has been repeated uncritically since. It was actually the Church itself, however, which preserved the Samhain tradition in the West by Christianizing it in the 9th century, setting the course for a pagan Northern European religious tradition's transformation into a worldwide secular holiday which has become the most popular – and commercially lucrative – of the year, second only to Christmas.

Samhain

Halloween traditions in the West date back thousands of years to the festival of Samhain (pronounced 'Soo-when', 'So-ween' or 'Saw-wen'), the Celtic New Year's festival. The name means "summer's end", and the festival marked the close of the harvest season and the coming of winter. The Celts believed that the veil between the worlds of the living and the dead was thinnest at this time and so the dead could return and walk where they had before. Further, those who had died in the past year and who, for one reason or another, had not yet moved on, could do so at this time and might interact with the living in saying good-bye.

Further, there was a very good chance that the spirit of a person one may have wronged would also make an appearance. In order to deceive the spirits, people darkened their faces with ashes from the bonfires (a practice later known as "guising"), and this developed into wearing masks. A living person would recognize the spirit of a loved one and could then reveal themselves but otherwise remain safe from the unwanted attention of darker forces.

All Hallows' Eve

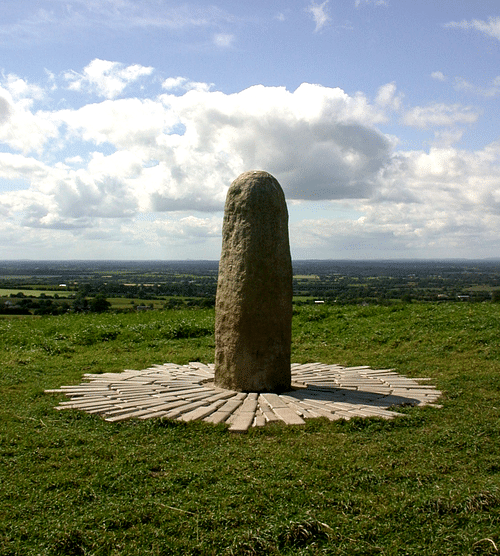

How long ago these rituals were included in the observance of Samhain is unknown, but some form of them were probably in place by the time Christianity came to Ireland in the 5th century. The hill of Tlachtga (Hill of the Ward) in County Meath was the site of the bonfire lighted on or around 31 October signaling the beginning of Samhain festivities when it was answered by the much more prominent fire from the Neolithic site of the Hill of Tara across from it. Archaeologists from University College Dublin have dated the excavated earthworks to 200 CE but note these are only the latest developments at a site first used for ceremonial fires over 2,000 years ago.

The hill is named for the druidess Tlachtga, daughter of the powerful druid Mug Ruith who traveled the world learning his craft. She was raped by the three sons of Simon Magus, infamous for his confrontation with St. Peter in the biblical Book of Acts 8:9-24, and gave birth to triplets on the hill that bears her name before dying there. The inclusion of a biblical villain in her story, obviously, places the legend in the Christian era and aligns Tlachtga with St. Peter in so far as they shared a common adversary. Scholars believe that the Tlachtga story, like so many Celtic legends, was Christianized after the coming of St. Patrick to Ireland and her rape by the sons of Simon Magus was added to a pre-existing account.

The Christianization of pagan symbols, temples, festivals, legends, and religious iconography is well established and applies to the Samhain festival as well as many others. Pope Boniface IV had set 13 May as All Saint's Day (All Hallows' Day), a feast day to celebrate those saints who did not have a day of their own, in the 7th century when he consecrated the great pagan temple of the Pantheon in Rome to Saint Mary and Christian martyrs, but in the 8th century, Pope Gregory III moved the date of the feast to 1 November. The motivation for this move is still debated. Some scholars claim it was done intentionally to Christianize Samhain by turning it into All Hallows' Eve, which is most likely true as the move follows an established Christian paradigm of "redeeming" all things pagan in an effort to ease the conversion process of a given population.

Prior to Christianization, 13 May had been the last day of the Roman festival of Lemuria (which ran 9, 11, 13 May), dedicated to placating the angry or restless dead. The festival developed from a pair of observances held earlier in the year, Parentalia – which honored the spirits of one's ancestors (13-21 February) – and Feralia – which honored the spirits of loved ones lost (21 February). On Feralia, the living were obligated to remember and visit the graves of the dead and leave them gifts in the form of grains, salt, bread soaked in wine, and wreaths, accompanied by violet petals.

Other Influences on Development

As it was with Parentalia, Feralia, Lemuria, and many others, so it was with Samhain. Previously, the Samhain festival was associated with all those who had gone on before, with the earth, and the change of the year; this transformation was marked by celebration and communal activities. Once the festival was Christianized, All Hallows' Eve became a night of vigil, prayer, and fasting in preparation for the next day when the saints were honored at a far tamer celebration.

The old ways had not died out, however, and bonfires were still lighted – only now in honor of Christian heroes – and the turning of the seasons was still observed – only now to the glory of Christ. Many of the rituals which accompanied this new incarnation of the festival are unknown but by the 16th century, the practice of "souling" had become integral. The poor of the town or city would go about knocking on doors asking for a soul-cake (also known as a soul-mass-cake) in return for prayers.

This practice is thought to have begun in response to the belief in purgatory where it was thought a soul lingered in torment unless elevated by prayer and, most often, money paid to the Church. After the Protestant Reformation, "souling" continued in Britain, only now the Protestant young and poor offered to pray for the people of the house and their loved ones instead of those in purgatory while Catholics continued the older tradition.

In the 17th century, Guy Fawkes Day added a new component to the development of Halloween. On 5 November 1605, a group of dissident Catholics tried to assassinate the protestant King James I of Britain in an attempt known as the Gunpowder Plot. The attempt failed and one of the group, Guy Fawkes, was caught with the explosives beneath the House of Lords and, although he had co-conspirators, his name attached itself famously to the plot.

Guy Fawkes Day was celebrated by the Protestants of Britain as a triumph over "popery", and 5 November became an occasion for anti-Catholic sermons and vandalism of Catholic homes and businesses even though, officially, the government claimed it was a celebration of Providence sparing the king. On Guy Fawkes night, bonfires were lit and unpopular figures – most often the Pope – were hanged in effigy while people drank, feasted, and set off fireworks. Children and the poor would go house to house, often wearing masks, pushing an effigy of Guy Fawkes in a wheelbarrow and begging for money or treats while threatening vandalism if they were refused.

Coming to North America

When the British came to North America, they brought these traditions with them. The Puritans of New England, who refused to observe any holidays which might be associated with pagan beliefs – including Christmas and Easter – kept the observance of Guy Fawkes Day on 5 November as a reminder of their supposed moral superiority to Catholics. Guy Fawkes continued to be celebrated up until the American Revolution of 1775-1783.

The rituals of Samhain arrived in the United States less than a century later with the displacement of the Irish in 1845-1849, during the potato famine. The Irish, largely Catholic, continued to observe All Hallows' Eve, All Saint's Day, and All Soul's Day along with the practice of "souling" but these festivals by now were infused with folk traditions such as the jack-o'-lantern.

Further Developments

The jack-o'-lantern is associated with the Irish folktale of Stingy Jack, a clever drunk and con man who fooled the devil into banning him from hell but, because of his sinful life, could not enter heaven. After his death, he roamed the world carrying a small lantern made of a turnip with a red-hot ember from hell inside to light his way. Scholars believe this legend evolved from sightings of will-o'-the-wisp, swamp and marsh gasses which glowed in the night. On All Hallows' Eve, the Irish hollowed out turnips and carved them with faces, placing a candle inside, so that as they went about "souling" on the night when the veil between life and death was thinnest, they would be protected from spirits like Stingy Jack.

The basics of Halloween were now in place with people going from house to house asking for sweet treats in the form of the soul-cakes and carrying jack-o'-lanterns. Shortly after their arrival in the United States, the Irish traded the turnip for the pumpkin as their lantern of choice as it was much easier to carve. Guy Fawkes Day was no longer celebrated in the United States but aspects of it attached themselves to the Catholic holidays of October, especially vandalism, only now it was indiscriminate: anyone's home or business could be vandalized around 31 October.

In the village of Hiawatha, Kansas, the morning after Halloween in 1912, a woman named Elizabeth Krebs grew tired of having her garden – and entire town – vandalized once a year by marauding children wearing masks and, initially using her own resources, organized a party in 1913 for the young people where, she hoped, she would tire them out enough that they would have no energy for destruction.

She underestimated their determination, however, and the community was vandalized as usual. In 1914, she involved the entire town, brought in a band, held a costume contest, and put on a parade – and her plan worked. People of all ages enjoyed a festive, rather than disruptive, Halloween. News of her success traveled outside of Kansas to other towns and cities which adopted the same course and established Halloween parties which included costume contests, parades, music, food, dancing, and sweet treats accompanied by frightening decorations of ghosts and goblins.

Although Mrs. Krebs is sometimes cited as the “mother of modern Halloween”, this is not entirely true as she did not institute the practice of going door-to-door asking for treats. This tradition was a few centuries old by the time she put on her first event. Mrs. Krebs' original vision definitely did impact how people in America celebrate Halloween, however, and the Halloween Frolic of Hiawatha, Kansas, continues to be observed annually along with the many similar festivals it inspired.

The party as a distraction from destruction, however, did not catch on nationwide and, by the 1920s, so-called "mischief night" had become a serious problem, not only in the United States but also in Canada. How, exactly, the practice of destroying people's property on the night of 31 October morphed into going door-to-door asking for candy in return for leaving a home in one piece is unclear, but it was already established in Canada by 1927 when a newspaper article from Blackie, Alberta, Canada featured a story about children going door-to-door in this way and is the first known appearance in print of the phrase "trick or treat". The children were given the candy and the homeowner was left in peace.

This tradition continued in North America throughout the 1930s, was interrupted by World War II owing to the sugar ration which dramatically cut the candy supply, and reemerged in the late 1940s. The familiar tradition of the present day dates to the 1950s and has steadily become popular in other countries, following the same basic paradigm. Today, Halloween is not generally associated with any particular religion or tradition and is commonly viewed as a secular community holiday, primarily focused on the young, and a boon for businesses offering candy and decorations as well as the entertainment industry which releases films, TV specials, and books on paranormal themes.

Central Theme

For many Neo-Pagans and Wiccans in the modern day, however, the holiday continues to be observed – as closely as possible – as it was in the ancient past. The central theme of Samhain was transformation. The year turned from the light days to the dark, the dead crossed over into the land of the living or moved on to the other side, people disguised themselves as other entities, and entities might appear as people, animals were slaughtered and turned into food while grains, fruits, and vegetables were similarly transformed for winter storage and wood and bone went up in the flames of the bonfires as smoke.

Transformation is still central to the observance of Halloween. The mask and costume transforms the wearer from their everyday life to another persona. For a night, one becomes Darth Vader or a zombie or the Great Pumpkin. The best-known, and most popular, costumes also touch on transformation. The werewolf is a human who changes into an animal; the vampire can vanish into smoke or become a bat; ghosts were once people.

In pre-Christian Ireland, the goddess most closely associated with Samhain was the Morrigan, the deity associated with war and fate who led her people, the Tuatha de Danaan, to freedom in a battle against the Fomorians. The Morrigan, in every one of her stories, is a transformative figure and in the story from the Irish epic Cath Maige Tuired she changes the fate of her people, making them their own masters instead of slaves of other forces.

The transformation was often frightening but could also be inspiring. The werewolf figure developed in response to fear of animal attacks and the vampire, perhaps, as a response to the fear of the angry dead who returned to torment the living. In these cases, however – and many others – it was within human power to kill the monster and so their legends can empower people to recognize their own strengths in the face of perilous circumstances.

The masks of Halloween and the present-day traditions represent this same theme and touch on the most basic aspects of the human condition and the ancient observance of Samhain. The costumes people wear represent fears and hopes in the same way the people centuries ago wore their masks to deter unwelcome spirits and experiences while anticipating joyful reunions with loved ones.

Many of the costumes represent the universal fear of death and the unknown which, for a night anyway, is mastered as one becomes that which one would normally dread and, transformed, neutralizes that fear. At its most basic level, Halloween is – or can be – a triumph of hope over fear, which is most likely what it also meant to the ancient Celts at Samhain thousands of years ago.

Bibliography

- Assorted Authors. New Catholic Encyclopedia. Gale Research Inc, 2010.

- Daimler, M. Gods and Goddesses of Ireland. Moon Books, 2016.

- Grimassi, R. Spirit of the Witch. Llewellyn Publications, 2003.

- Guy Fawkes Day: A Brief History by Jesse GreenspanAccessed 19 Mar 2020.

- History Mysteries at the Museum: Elizabeth Krebs by Lynn Allen BrownAccessed 19 Mar 2020.

- Hoffner, H. Catholic Traditions and Treasures. Sophia Institute Press, 2018.

- Morton, L. Trick or Treat: A History of Halloween. Reaktion Books, 2019.

- Rees, A & B. Celtic Heritage. Thames and Hudson, 1989.

- Rolleston, T. W. Celtic Myths and Legends. Dover Publications, 1990.

- Squire, C. Celtic Myths & Legends. Portland House Publishers, 1994.

- The History of Trick Or Treating Is Weirder Than You Thought by Rose EvelethAccessed 19 Mar 2020.

- The Role of the Morrigan in the Cath Maige Tuired: Incitement, Battle Magic and Prophecy by Morgan DaimlerAccessed 19 Mar 2020.

About the Author

Translations

ARABIC FRENCH GREEK ITALIAN MALAY PERSIAN PORTUGUESE SPANISH TURKISHWe want people all over the world to learn about history. Help us and translate this article into another language!

Questions & Answers

What is the origin of Halloween?

- Halloween's origins trace back to the Celtic celebration of Samhain (pronounced "sou-when") when the veil between the living and the dead was thought to be thinnest and souls passed between realms.

What is the earliest observance of Halloween in the USA?

- The earliest observance of Halloween in the USA was in Hiawatha, Kansas, in 1914. It was organized by Elizabeth Krebs, known as the Mother of Modern-Day Halloween.

When did trick-or-treating start?

- The earliest mention of the phrase "trick or treat" and a description of the practice comes from a Canadian newspaper article in 1927.

What is the meaning of Halloween?

- Transformation. At Halloween, the souls of the dead are thought to walk among the living, the living put on costumes and become other people or things, treats are passed between people, fires are lighted and food is shared -- all aspects of transformation.

Free for the World, Supported by You

World History Encyclopedia is a non-profit organization. For only $5 per month you can become a member and support our mission to engage people with cultural heritage and to improve history education worldwide.

Recommended Books

World History Encyclopedia is an Amazon Associate and earns a commission on qualifying book purchases.External Links

Cite This Work

APA Style

Mark, J. J. (2019, October 21). History of Halloween. World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://www.worldhistory.org/article/1456/history-of-halloween/

Chicago Style

Mark, Joshua J.. "History of Halloween." World History Encyclopedia. Last modified October 21, 2019. https://www.worldhistory.org/article/1456/history-of-halloween/.

MLA Style

Mark, Joshua J.. "History of Halloween." World History Encyclopedia. World History Encyclopedia, 21 Oct 2019. Web. 24 Jul 2023.